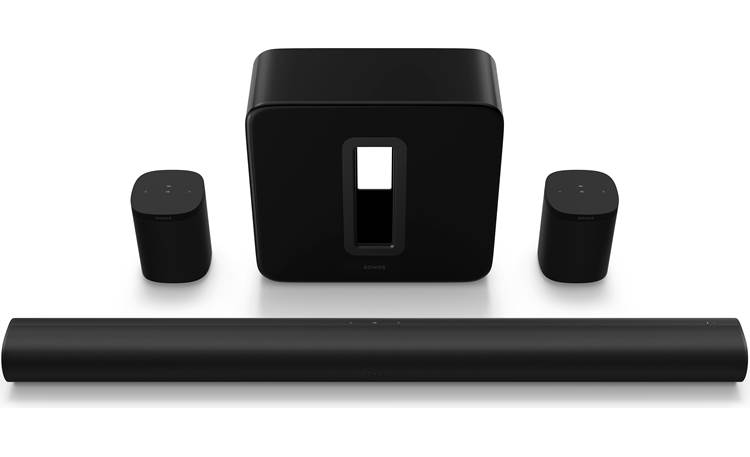

Sonos Arc 5.1.2 Home Theater Bundle (Black) Includes Sonos Arc Dolby Atmos® sound bar, Gen-3 Sub, and two Sonos Ones at Crutchfield

How to decide between two HomePods or a Sonos system for a home theater - General Discussion Discussions on AppleInsider Forums

Sonos Era 300: Dolby Atmos, no bigger than a bread box | Esquire Middle East – The Region's Best Men's Magazine

Sonos Amp review: This is the best Sonos music streamer by far (even if it's not right for everyone) | TechHive